A few weeks ago, I bought myself the Bing Crosby double feature dvd, Rhythm on the River/Rhythm on the Range. Now, I’m not a huge Bing fan–I like him in High Society (1956) and of course with my love for Fred Astaire, Holiday Inn (1942) ranks pretty high on my list (But not Blue Skies (1946)–I think that one is pretty dull).

A few weeks ago, I bought myself the Bing Crosby double feature dvd, Rhythm on the River/Rhythm on the Range. Now, I’m not a huge Bing fan–I like him in High Society (1956) and of course with my love for Fred Astaire, Holiday Inn (1942) ranks pretty high on my list (But not Blue Skies (1946)–I think that one is pretty dull).

I mainly wanted to see Rhythm on the River because of Oscar Levant. Yes, I’ve mentioned it before, but I’ll mention it again: I love him. Even though he’s more of a personality than an actor, he’s still one of my favorites. With the exception of one or two movies, I think I’ve seen most of his filmography.

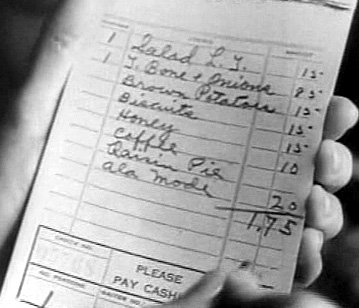

Rhythm on the River (1940) is a cute little movie, and surprisingly it’s co-written by the great Billy Wilder. It’s plot revolves around a “brilliant” singer-songwriter named Oliver Courtney (Basil Rathbone), who in reality, can’t write music or lyrics to save his life. The real geniuses behind his popular hits are Bob Sommers (Bing Crosby) and Cherry Lane (Mary Martin). Of course, neither know each other exist and when the finally meet, they fall in love. Together, Bob and Cherry defect from Courtney’s employment and try to strike out on their own, only to be rejected by every publisher in town because their songs sound too much like Courtney’s. Oscar Levant plays Courtney’s musical assistant, Starbuck (when you needed a sarcastic, wisecracking piano player, Levant was your man) and there’s a cute little joke revolving around a bed and breakfast inn that Crosby’s folks own called, “Nobody’s Inn.” Get it? Nobody’s In? Ha ha! Anyway, Rhythm on the River predates Holiday Inn by two years, so it seems like they took the idea from this movie and just expanded on it.

Rhythm on the River (1940) is a cute little movie, and surprisingly it’s co-written by the great Billy Wilder. It’s plot revolves around a “brilliant” singer-songwriter named Oliver Courtney (Basil Rathbone), who in reality, can’t write music or lyrics to save his life. The real geniuses behind his popular hits are Bob Sommers (Bing Crosby) and Cherry Lane (Mary Martin). Of course, neither know each other exist and when the finally meet, they fall in love. Together, Bob and Cherry defect from Courtney’s employment and try to strike out on their own, only to be rejected by every publisher in town because their songs sound too much like Courtney’s. Oscar Levant plays Courtney’s musical assistant, Starbuck (when you needed a sarcastic, wisecracking piano player, Levant was your man) and there’s a cute little joke revolving around a bed and breakfast inn that Crosby’s folks own called, “Nobody’s Inn.” Get it? Nobody’s In? Ha ha! Anyway, Rhythm on the River predates Holiday Inn by two years, so it seems like they took the idea from this movie and just expanded on it.

Besides Oscar, it was Mary Martin who intrigued me the most. While she’s a good singer, I didn’t find her to be an outstanding actress. But she’s cute enough and the interaction between her and Bing was realistic. However, the most striking thing about her was her resemblance to Jean Arthur.

Back when the lovely and talented Ms. Arthur was TCM’s Star of the Month (in January ’07, I believe), I bought a biography on her called The Actress Nobody Knew by John Oller. It was certainly a page-turner, filled with all kinds of interesting information that spanned her entire career. Believe it or not, she and Oscar Levant were once an item in the late 20’s! Jean had called him, “The only brain in Hollywood” and when they went out, he accompanied her to speakeasies and prize fights, that is, if they weren’t cozied up in the corner at a party.

However, one of the most interesting stories in the book is her supposed relationship with Mary Martin. They first met in 1939 at a small dinner party, shortly after Mary came to Hollywood. The meeting wasn’t exactly a happy experience for her–Jean spent the evening in deep conversation with Paramount story editor, Richard Halliday and completely ignored Mary. Despite this, Halliday married Martin a short while later and soon enough, they became good friends and neighbors to Jean and her husband, Frank Ross.

The friendship between Jean and Mary quickly grew. Not only did they spend a great deal of time together, but they also shared an obsessive love for Peter Pan. The women would endlessly discuss their dream of playing the character one day and when they planned to attend costume parties, Jean and Mary would fight over which one would get to dress up as Peter Pan. Both ladies would get to play the part: Jean would play it on Broadway in 1950, and Mary in 1954 but through the years, it’s Mary who’s mostly associated with the role.

Hollywood gossips noted the close friendship between the two ladies, and soon enough, rumors that they were romantically involved began to swirl around town. Not helping matters was Mary’s startling resemblance to Jean! If you’re a classic movie fan with only a smattering of knowledge, you may think that it’s Jean Arthur in Rhythm on the River, not Mary Martin! And if that weren’t enough, Mary’s career seemed to follow Jean’s: both ladies would play female western legends (Jean was Calamity Jane, while Mary was Annie Oakley on stage) as well as the Billie Dawn role in Born Yesterday (Jean briefly played it on stage, while Mary did the tv version).

Hollywood gossips noted the close friendship between the two ladies, and soon enough, rumors that they were romantically involved began to swirl around town. Not helping matters was Mary’s startling resemblance to Jean! If you’re a classic movie fan with only a smattering of knowledge, you may think that it’s Jean Arthur in Rhythm on the River, not Mary Martin! And if that weren’t enough, Mary’s career seemed to follow Jean’s: both ladies would play female western legends (Jean was Calamity Jane, while Mary was Annie Oakley on stage) as well as the Billie Dawn role in Born Yesterday (Jean briefly played it on stage, while Mary did the tv version).

In late 1966, Hollywood thought the rumors were practically confirmed when an obscure publisher released a novel entitled, The Princess and the Goblin (not having anything to do with the fairy tale of the same name). Written by Paul Rosner, the story described the intertwining lives of two actresses, Maureen and Josie. Like Mary, Maureen was a star on Broadway and arrived in Hollywood in the late ’30’s. She then falls in love with Josie, her female idol. Josie, like Jean, is a publicity shy actress, whose husky voice and comedic talent elevated her as one of Hollywood’s top leading ladies. The two women soon have an affair, which causes Josie to have a nervous breakdown and therefore become a recluse. After its publication, the rumors spread like wildfire. Everyone in Hollywood assumed that Rosner was confirming the gossip about Jean and Mary (it doesn’t help that their fictional characters even share the first initial of their names!).

But there was one glitch–Rosner had created a total work of fiction. Yes, he had based the character of Josie on Jean and Maureen on Mary, but only through his own viewing of Jean’s films and his observation on how Mary had seemingly usurped Jean’s identity. When Rosner saw Mary as Peter Pan, a light bulb clicked. The physical similarities (minus the husky voice) between Jean and Mary were downright eerie. After the novel’s publication, he was surprised by the amount of phone calls and feedback he received: people had assumed that he was writing a thinly veiled story of truth, not fiction. Rosner once commented, “I had no way of knowing when I wrote it that any of it was true.”

If Jean knew about the book, she never let anyone know. The only reference she made towards it’s existence was during her teaching days at Vassar college in the early 70’s. While heading a drama class, Jean had her students recreate a scene from Lillian Hellman’s controversial play, The Children’s Hour, in which a vicious child falsely accuses her two female teachers of being lovers. When the students finished the scene, Jean was visibly upset and explained to her class on how gossip can ruin one’s life. Was she referring to The Princess and the Goblin and/or the Mary Martin rumors? No one will ever know. While many books written after her death state that Jean was a lesbian (despite being married to Frank Ross for seventeen years!), it seems as though she was asexual. In a 1975 interview, Jean stated that sex was something she could live without. Her friend and one time agent, Helen Harvey, claimed that Jean’s passions were more geared towards her strict ideals, while another male friend said that she had little interest in romance, since most of the time her head was in the clouds. Jean’s world wasn’t one that was firmly rooted in reality. She chose her own path and did her own thing. And for some reason, people love to speculate about those who are uninterested in following the standards of society–especially if an unmarried woman chooses to live her life alone.

If Jean knew about the book, she never let anyone know. The only reference she made towards it’s existence was during her teaching days at Vassar college in the early 70’s. While heading a drama class, Jean had her students recreate a scene from Lillian Hellman’s controversial play, The Children’s Hour, in which a vicious child falsely accuses her two female teachers of being lovers. When the students finished the scene, Jean was visibly upset and explained to her class on how gossip can ruin one’s life. Was she referring to The Princess and the Goblin and/or the Mary Martin rumors? No one will ever know. While many books written after her death state that Jean was a lesbian (despite being married to Frank Ross for seventeen years!), it seems as though she was asexual. In a 1975 interview, Jean stated that sex was something she could live without. Her friend and one time agent, Helen Harvey, claimed that Jean’s passions were more geared towards her strict ideals, while another male friend said that she had little interest in romance, since most of the time her head was in the clouds. Jean’s world wasn’t one that was firmly rooted in reality. She chose her own path and did her own thing. And for some reason, people love to speculate about those who are uninterested in following the standards of society–especially if an unmarried woman chooses to live her life alone.

As for Mary Martin, she was married twice–first to Ben Hagman, before marrying Richard Halliday, whom she remained with until his death in 1973. Despite this, rumors about her sexuality have always dogged her, even claiming that the great love of her life was actress, Janet Gaynor. The two women were close friends, and both were involved in a tragic car accident that occurred in 1982. While it left Mary bruised and injured, Janet was critically hurt and the multiple injuries led to her death in 1984.

As for Mary Martin, she was married twice–first to Ben Hagman, before marrying Richard Halliday, whom she remained with until his death in 1973. Despite this, rumors about her sexuality have always dogged her, even claiming that the great love of her life was actress, Janet Gaynor. The two women were close friends, and both were involved in a tragic car accident that occurred in 1982. While it left Mary bruised and injured, Janet was critically hurt and the multiple injuries led to her death in 1984.

What I always find odd about classic Hollywood rumors are the fact that they seem to come out after a person has died. It tends to be awfully convenient, since it’s hard for a ghost to defend itself. I’ll be the first person to admit that I enjoy reading about my favorite actors and actresses, and yes, that includes the gossipy bits. I don’t think this makes me less of a fan though–I’m just a nosy person! Still, I don’t base my love of certain actors/actresses/directors on gossip. I judge them by their performances. For example, I dislike Grace Kelly not because of all the men she hopped into bed with, but because I think she’s mostly a lousy actress (Dial M For Murder an exception – please direct all your hate mail to the email address at the top of the sidebar! Thank you!).

In Rhythm on the River, I admit that I loved Oscar Levant’s Starbuck character the most, but since that was to be expected, I can also add Mary Martin to my list. As I mentioned before, I don’t think she was an outstanding actress, but she was pleasant to watch. I’ve read some fan postings which claim that her talent never translated well to the big screen and in order to really see her shine, one had to see in her element–that is, Broadway. I can fully understand that. Most stage actors don’t translate well to motion pictures, which is why they stay on the stage. Still, if I saw Mary Martin’s name in the opening credits of a film, I certainly would watch. Mary’s acting style was fun and cute and for the type of breezy musical comedies Paramount cast her in, her personality was a perfect fit.